Building a Customer-Centric Culture: what it means

Getting rid of processes to create mature design practices that lead to customer centrici

Hi, I'm Raff Di Meo. I'm a Product Designer with over ten years of experience. The products I have designed are used by the biggest retailers in the world, from Amazon, Adidas, Uniqlo, Nespresso and more. I started this publication to help designers start and grow in their careers by sharing tips, advice, and insights about design.

You have studied UX design, read books and blogs, taken workshops, and attended conferences. Your LinkedIn timeline is filled with content about UX processes, showing you what’s the ‘new’ way of doing UX design.

The pressure in the design world is tangible, and you must ensure you are better than a machine at design. AI is coming to steal your job.

But, if you want to find the proper way of doing UX - whatever that means - you better not google it; the internet is a jungle.

It seems that the only way to achieve great results as designers is to aspire to implement an outstanding design process. The pressure on processes is also evident during interviews when we are asked about it constantly.

What if we move away from processes and look at other factors to improve our design practice? Following the ‘correct’ process is not a symptom of a customer-centric business.

As part of the series, we first analyse what we mean by design processes, and then we explore the concept of design maturity and why it is vital for businesses; in the end, we uncover practical steps that we can take to create a customer-centric culture, and I share more about my experience.

Let’s start from the beginning, talking about the design process.

The Design Process: textbook

If you have wondered what process to use when doing UX, the answer is straightforward. All the processes you find in books and online are the same and are all based on User Centre Design (UCD). Debbie Levitt’s article explains it incredibly well by exploring (and mocking!) ten different processes.

As long as you stick to a few main principles, the name doesn’t matter.

Understand the problem to solve

Create a solution

Test it

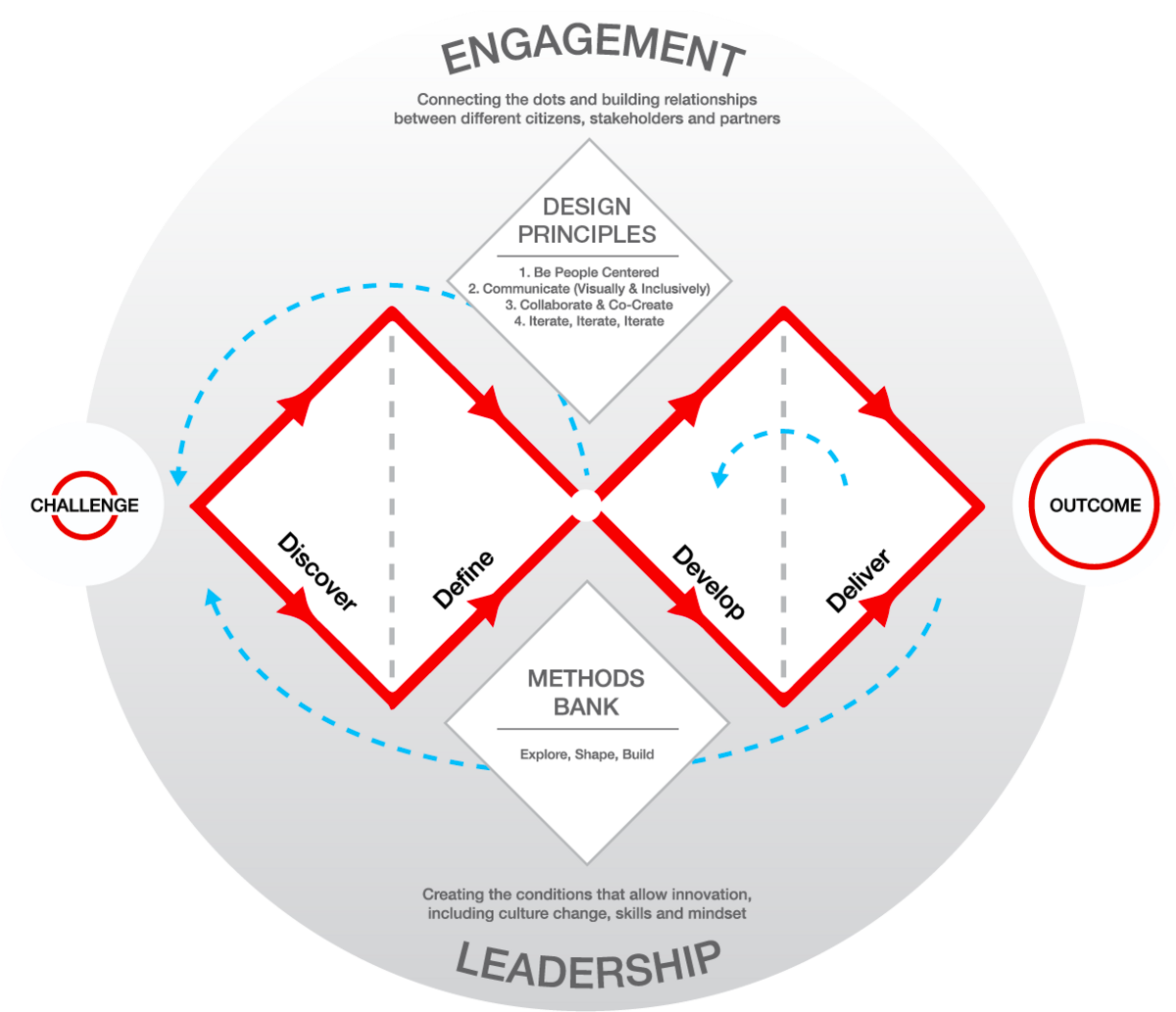

The most well-known design process is the Double Diamond, created by the Design Council. This is based on UCD, providing clear phases to take you from problem to solution.

The fundamental of this process is like any UX process:

Understand the problem. Your business might have an assumption or a real issue connected to a product or a service. You can delve further into the problem through user research.

Define the problem. Once you have researched the problem, you can start defining it based on the insights gathered. This helps narrow down your problem area.

Design the solution. It’s now time to design your solution and explore different ways that you can solve the problem.

Test. When confident with a solution, you can gather further user insights by testing it. Then, you create more designs and test them until you have a solution that fits your user needs and helps the business achieve its goals.

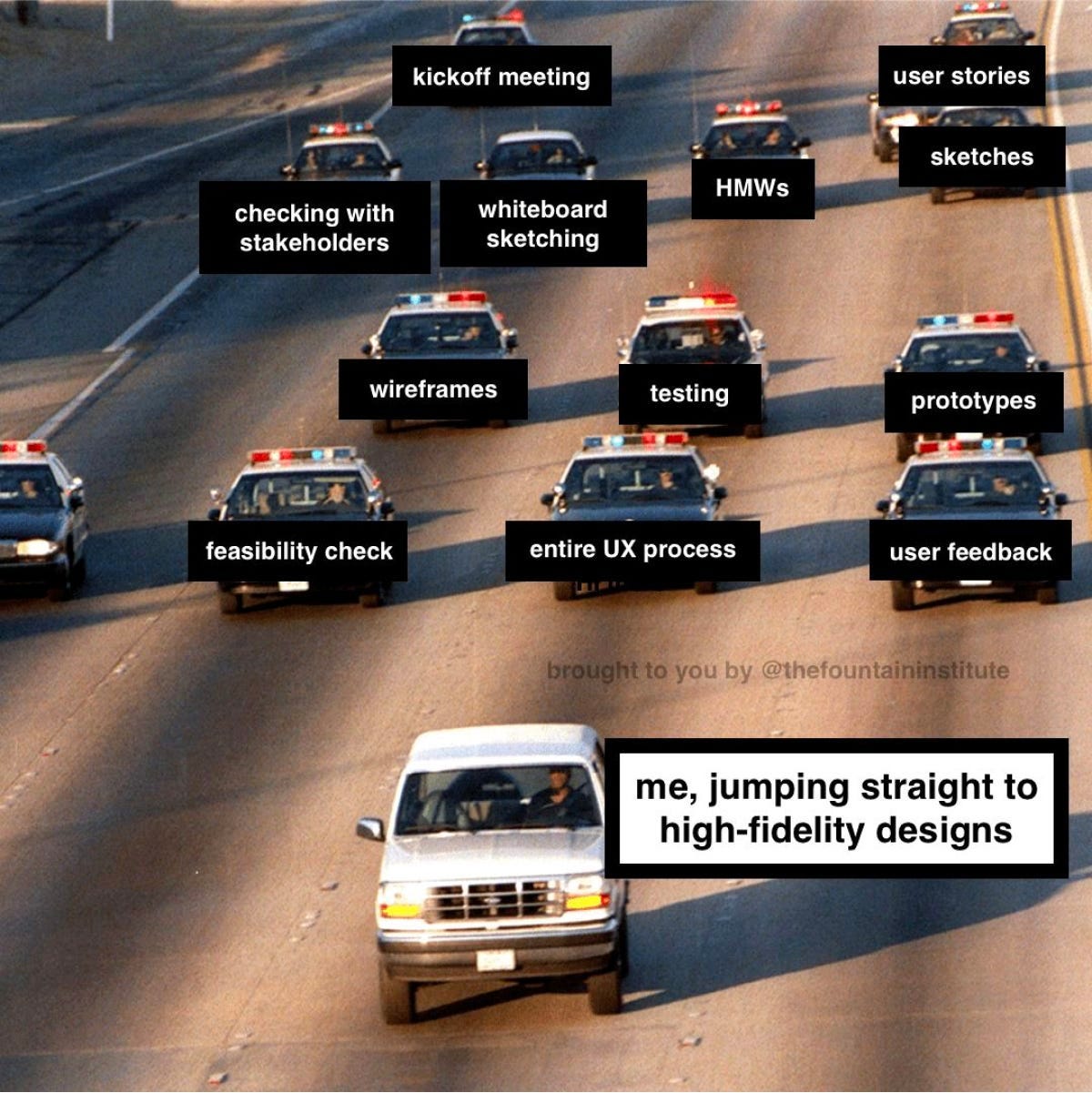

The Design process: real world

You are probably thinking that you do not always go through those steps. Sometimes, you are given a defined problem to solve and start designing immediately. On other projects, the time allowed for generative research is just a few days at the beginning of the sprint, so you only have the time to do basic desk research. You are not alone!

Many businesses do not have well-defined product development processes and do not understand the value that research and design can add to generate revenue, find product market fit, or whatever their goals are.

This generates low job satisfaction among designers, who are frustrated because they spend most of their time fighting for better processes or just get bored pushing pixels rather than contributing to understanding the problem and finding the right solution.

When we look at design processes, they feel like a utopia. We can’t get all those steps in place in our projects. The reality, though, is that we don’t really have to.

Applying a UCD approach will vary depending on the project and the business. Sometimes, the company already has tons of knowledge in a problem area, and you are working on contained scenarios. Therefore, you might decide that you do not need to run extensive research. Other times, you might work on an entirely new product and decide to run comprehensive research to understand more about the problem area.

As long as you keep close to your users, relying on internal knowledge, going straight to design or conducting extensive generative research are all great ways to design with UCD in mind.

Break the UX design process

Business problems are different and do not always require the same level of research, definition, design and testing.

So, if the design process isn’t always the same, it doesn’t matter, and it’s probably a good thing. Even if a good understanding of a design process is essential, you must use your critical thinking to evaluate the best process to get to the solution.

In his article, Ben Brewer provides many examples of moving the focus from sticking to a design process to having a series of tools that designers can use depending on the problem. He focuses on understanding the knowledge around a specific problem space and its associated risks. Based on these factors, designers can evaluate the best tools to use to get to an optimal solution. The more the risk, the more research is needed.

Scenario 1

Suppose you have problems with many unknowns and a high degree of risk. In that case, you might want to invest more time in generative research to understand the users and the market better, aiming to find ways to summarise the context for the business.

Scenario 2

If the risk is high, but you have a good understanding of the problem space, you might want to spend less time on generative research and go straight into mapping out the problem and creating initial ideas on how to solve it. Be careful, as most companies think they know the users and the market well when, realistically, that’s not always the case.

Scenario 3

With problems that are low risk and within your problem space, you can feel more confident in creating something straightaway and testing it out with users, gathering data and iterating on them.

With a design tool approach, you can be more flexible in identifying the best starting point for building a customer-centric culture in your organisation.

Customer centricity

Now that we are less focused on the process and more on solving problems in the best and most efficient way possible let’s look at the concept of design maturity as a basis to take the business towards a more customer-centric culture.

The NN/g group defines design maturity as the ‘[…]quality and consistency of research and design processes, resources, tools and operations, as well as the organisation's propensity to support and strengthen UX now and in the future through its leadership, workforce and culture.’

As you can see from this definition, the design process makes an appearance, but it’s not everything you need for a mature design practice. It’s about quality and consistency, as well as supporting and strengthening the value and role of UX.

Why are we talking about design maturity?

I think design maturity is crucial for teams just getting started and finding their feet in organisations that aren’t aware of what customer-centricity means for them. That’s the position I have found myself in quite a few times!

When we have a business that gets designs and its value, it allows teams to connect to their users and not just create screens. Designers who are closer to customers can help the business make a difference. So, if we elevate our design practice and mature, we can be more customer-centric. This article from Reforge articulates much better than I could do.

The question then is how do we get to a more mature design practice that allows designers to understand customer’s problems deeply?

The following article will dive further into design maturity, exploring models and why customer-centricity is vital for businesses to succeed. Then, the series will get into the practical tips you can put into practice; they worked for me, and I hope they work for you, too.